January 7, 2024 – My day began with an unexpected adventure, one that left me caked in mud after getting stuck in the Menabilly car park. Not exactly how I’d planned to start my visit! After freeing myself from the muddy situation, I made a quick stop at a petrol station to gather some essential supplies—paper towels, garbage bags, and water—to clean off the mess. With shoes and car mats still muddy, I found a quiet car park in Mevagissey to tidy up before heading to Heligan for Sunday Roast. I couldn’t help but chuckle at the thought of showing up covered in mud—what a way to make an entrance! But, as with all good adventures, it’s a story I’ll be telling for a long time.

After navigating the narrow streets of Mevagissey, I arrived at The Lost Gardens of Heligan around 2 p.m. Despite it being a Sunday afternoon, the car park was bustling with activity.

What Are The Lost Gardens of Heligan?

Nestled within the historic Heligan estate, the manor’s origins trace back to the late 13th century with the Heligan family. Since 1569, the estate served as the ancestral seat of the Tremayne family for over 400 years. However, when Jack Tremayne moved to Italy around 1920, the once-thriving gardens fell into neglect. The onset of the Great War further deepened the estate’s decline. After Jack Tremayne’s passing in 1949, the house and gardens were placed in a trust to benefit the Tremayne family. The house was divided into apartments and sold, but the gardens remained under the trust’s protection.

In 1990, John Willis, a descendant of the Tremayne family, and Sir Tim Smit, discovered the long-forgotten gardens and led efforts to restore them to their former glory. This restoration not only revived the beauty of Heligan but also paid tribute to the lives of the gardeners who once worked there before the war. Today, the Lost Gardens of Heligan span 200 acres and welcome over 350,000 visitors annually.

Historic England | Spotlight on Heligan

A Family Connection

As I explored the gardens, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own family’s ties to Heligan:

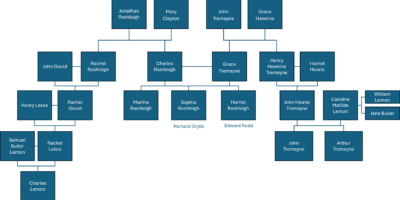

Grace Tremayne, who married Charles Rashleigh, is my 6th great aunt. Charles was the younger brother of Rachel Rashleigh, my 6th great-grandmother, who married John Gould, MD. Their lineage connects through generations to my maternal grandmother, Anne, or as I remember her – Nana. These are the Rashleighs of Menabilly.

John Hearle Tremayne, son of Rev. Henry Hawkins Tremayne and Harriet Hearle, married Caroline Lemon. Caroline was a cousin of mine, through the Lemon family of Carclew. John Hearle Tremayne inherited Heligan in 1829, and his own son John succeeded him in 1851. Another son, Arthur Tremayne, inherited Carclew from his uncle, Sir Charles Lemon, in 1868. This Carclew-Heligan connection explains how the Carclew gates found their way to Heligan.

John Claude Lewis ‘Jack’ Tremayne was the last Tremayne to reside at Heligan House before moving to Italy in the 1920s. Around 1900, Jack was briefly married to Eleanor Rashleigh, the daughter of Jonathan Rashleigh of Menabilly. Jonathan was the great-nephew of Charles and Rachel Rashleigh, the latter being my 6th great-grandmother.

Flora and Fauna

As I passed through the gates, the diversity of plants surrounding the lot immediately caught my eye. Right next to my car, pink camellias with dark green, serrated leaves welcomed me to Heligan.

Before leaving Canada, I had reserved a table for the traditional English Sunday Roast at the estate’s restaurant, mentioning that I was visiting to explore my family’s connection to Heligan. The Restaurant Manager graciously introduced me to Candy Smit, Heligan’s Historian and Archivist.

Candy met me along the foliage-lined path to the restaurant, where we were seated by a warm fireplace in the cozy dining room. The Sunday Roast, my first, was a revelation—every bite was simply out of this world. As we dined, Candy shared how Heligan has become a model of sustainable farming, with all the food grown or reared on their working farm. It was farm-to-table in the truest sense. During our meal, Candy introduced me to her former husband, Sir Tim Smit, who is also renowned as the co-founder of The Eden Project, a world-class horticultural complex in a reclaimed china clay pit.

After our meal, we embarked on a walking tour of the grounds, beginning in the Northern Gardens by Flora’s Green. The magnificent array of camellias and rhododendrons, some planted over 150 years ago, was in all sense of the word, breathtaking. We encountered a lady who fondly recalled her father packaging flowers for Kew Gardens and shared memories of growing up on the estate, including venturing into the basement of Heligan House.

We continued through the Kitchen Garden, the walled Flower Garden, and the Melon Yard, where the pineapple pit and a banana tree flourish in greenhouses.

The Heligan Pineapple Pit

One of the most remarkable discoveries during the restoration of The Lost Gardens was the Victorian pineapple pit. In the 19th century, pineapples were considered a luxury item and were notoriously difficult to grow in the cooler British climate. However, the gardeners at Heligan developed an ingenious method to cultivate them using a pit heated by decomposing manure.

The pit was rediscovered in a dilapidated state but was restored to working order as part of the garden’s revival. Today, it remains one of the few functioning pineapple pits in the world, symbolizing the resourcefulness and creativity of the estate’s original gardeners.

The Family Connection

As we made our way to the Steward’s House, we paused to admire a rhododendron named after a cousin, Sir Charles Lemon. It reminded me of the connections between Heligan and Carclew, much like the familial ties that bind us.

Upon reaching the Steward’s House, we ascended to the Library, where we shared research notes. Candy showed me intricately drawn family trees linking the Tremayne, Lemon, and Rashleigh families. To my surprise, she retrieved a carefully-wrapped bundle of small diaries, handing me the personal diaries of my 6th great-aunt, Grace (Tremayne) Rashleigh. Holding these diaries, with entries dating back to the late 1770s, was a moment I’ll never forget. My jaw dropped as I carefully opened a diary from 1776, marveling at its near 250-year-old pages.

One entry, dated Thursday, March 21, 1776, caught my eye:

“Doctor Gould and his little boy dined here.”

Doctor Gould, my 6th great-grandfather, was dining with his son, John. It was as if history had come to life, right there in my hands. Another entry from Sunday, September 1, 1776, read:

“At church in the morning. We drank tea at the old Mrs. Polkinghorne’s, Doctor and Mrs. Gould also there. Mr. Rashleigh came here in the evening.”

These simple sentences transported me back to a specific moment in my family’s history—a truly unforgettable experience.

After a short walk back to the car park, Candy and I parted ways, and I began the two-hour drive back to Penzance, the dusk giving way to night.

I’m deeply grateful to Candy, Tim, and the entire team at The Lost Gardens of Heligan for preserving the stories of the past and working towards a more sustainable future.

If you’re enchanted by stories of hidden histories and magnificent gardens, then The Lost Gardens of Heligan should be at the top of your travel list. From the Victorian pineapple pit to the stunning views over the Cornish landscape, there’s so much to explore and experience. Whether you’re a history buff, a gardening enthusiast, or simply in search of a peaceful escape, Heligan offers something truly special.

So why not make plans to visit and discover the magic for yourself? I know I’m already planning my next trip!